Summary

The U.S. Supreme Court on Wednesday, March 22, 2017, issued their opinion on Star Athletica v. Varsity Brands. The Court affirmed the 6th Circuit, holding that the lines, chevrons, and colorful shapes of Varsity’s cheerleading uniforms were “conceptually separable” and eligible for copyright protection. The Court clarified the appropriate test to use in such cases, articulating a two-part test for whether a feature incorporated into the design of a useful article is eligible for copyright protection: (1) the feature can be perceived as a two- or three-dimensional work of art separate from the useful article, and (2) the feature would qualify as a protectable pictorial, graphic, or sculptural work—either on its own or fixed in some other tangible medium of expression—if it were imagined separately from the useful article into which it is incorporated.

Background of the Case

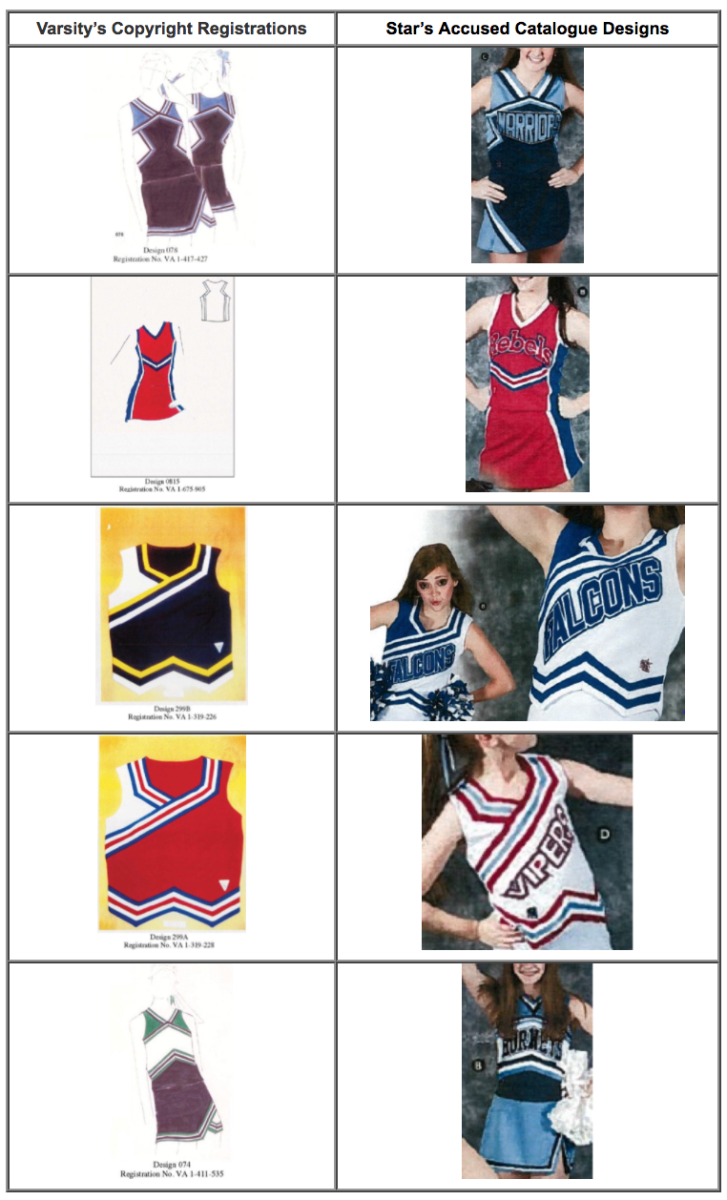

Varsity Brands, a large provider of cheerleading supplies, received U.S. copyright registrations for “two-dimensional artwork” on the five designs below. Varsity sued Star Athletica in July of 2010 alleging that Star’s cheerleading uniforms infringe these copyrights:

To qualify for copyright protection, the creative elements of a garment must be “conceptually separable” from the functional or “useful” elements. However, this “conceptually separable” test has been applied in numerous different ways depending on the court deciding the case.

On March 1, 2014, the Western District of Tennessee entered summary judgment for Star Athletica on the ground that Varsity’s designs were not eligible for copyright protection. The District Court reasoned that it was not possible to “physically or conceptually” separate the designs from the useful or “utilitarian” function of identifying the garments as cheerleading uniforms.

The case was appealed to the 6th Circuit, which reversed the District Court decision in August of 2015. The 6th Circuit held that the creative elements of Varsity’s designs were separable, warranting copyright protection. The 6th Circuit opinion acknowledged that there is conflicting precedent and that there are at least nine different tests used by different districts and the Copyright Office to decide the issue of “conceptual separability.” Even the dissent in the 6th Circuit decision implored either Congress or the Supreme Court to clarify the appropriate test.

The Supreme Court granted certiorari on the following question:

Under the Copyright Act, a “useful article” such as a chair, a dress, or a uniform cannot be copyrighted. 17 U.S.C. § 101. The article’s component features or elements cannot be copyrighted either, unless capable of being “identified separately from, and . . . existing independently of, the utilitarian aspects of the article.” Id. Circuit courts, the Copyright Office, and academics have proposed at least nine different tests to analyze this separability. The Sixth Circuit rejected them all and created a tenth. The first question is: What is the appropriate test to determine when a feature of a useful article is protectable under § 101 of the Copyright Act?

Decision

Justice Thomas issued the decision joined by Chief Justice Roberts and Justices Alito, Sotomayor, Kagan, and Ginsburg. Justice Ginsburg added her own concurring opinion, while Justices Breyer and Kennedy dissented. The 6-2 Court held that:

a feature incorporated into the design of a useful article is eligible for copyright protection only if the feature:

(1) can be perceived as a two- or three-dimensional work of art separate from the useful article and

(2) would qualify as a protectable pictorial, graphic, or sculptural work—either on its own or fixed in some other tangible medium of expression—if it were imagined separately from the useful article into which it is incorporated.

Regarding the first prong of the test, the Court explained that separate identification “is not onerous” and merely requires that the article have two- or three- dimensional element(s) that appear to have pictorial, graphic, or sculptural qualities.

The Court noted that the second prong regarding “independent existence” may be more difficult to satisfy. Specifically, the separately identified feature must have the “capacity to exist apart from the utilitarian aspects of the article.” The feature must be able to exist as its own work of art and cannot itself be a useful article. The Court used an example of a cardboard model of a car, which would not qualify for this independent existence prong. The replica itself could be copyrightable, but it would not confer any rights in the useful article, the car, that inspired it.

In establishing this test, the Court abandoned the distinction between “physical” and “conceptual” separability adopted by some courts and commentators. The Court noted that separability is a conceptual undertaking limited by the perception of the feature in which copyright is claimed, and the article to which it is affixed. Copyrightability does not depend on whether the identified feature can be physically separated from the useful article; nor does it depend on how or why the article or feature was designed, or on the marketability of the article or its features. The Court held that interpretation of the Copyright Act makes “clear that copyright protection extends to pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works regardless of whether they were created as free-standing art or as features of useful articles.”

The Court held that Varsity Brands’ cheerleader uniforms shown above meet this test and qualify for copyright protection.

The Court explained that the lines, chevrons, and colorful shapes appearing on the surface of Varsity’s cheerleading uniforms can be identified as decorations having pictorial, graphic, or sculptural qualities, meeting the first prong of the test. Additionally, the colors, shapes, stripes, and chevrons of the Varsity uniforms would qualify as two-dimensional works of art if they were separated from the cheerleader uniforms and applied to another medium, such as a painter’s canvas or different types of clothing. Thus, the second prong of the test is also met.

The Court expanded on this, noting that just because Varsity’s two-dimensional artwork may retain the outline of a cheerleading uniform does not bar it from being eligible for copyright protection. Similarly, two-dimensional fine art matches the shape of the canvas it is painted on and two-dimensional applied art corresponds to the contours of the article to which it is applied. Accordingly, the surface designs on the Varsity uniforms are eligible for copyright protection.

Justice Ginsburg concurred in the judgment but disagreed with the majority’s consideration of the “conceptual separability” test. Justice Ginsburg asserted that the designs at issue were “themselves copyrightable pictorial or graphic works reproduced on useful articles” reasoning that the designs first appeared as pictorial and graphic works sketched on paper by Varsity’s design team and were later reproduced on garments. As such, she contended that it was not necessary to consider the separability of the designs.

Justice Breyer and Justice Kennedy dissented, asserting that the designs are not eligible for copyright protection because they are pictures of cheerleader uniforms, which are useful articles, and the design features that Varsity seeks to protect are not “capable of existing independently of the utilitarian aspects of the article.” The dissent argued that placing the designs on another medium would result only in pictures of cheerleading uniforms. The majority opinion addressed Breyer’s criticism, distinguishing the design as “a two-dimensional work of art that corresponds to the shape of the useful article to which it was applied.”

Observations

This decision should make it easier to enforce companies’ copyrighted fashion designs; however, it is even more important for companies to obtain copyright registrations for their original designs. A copyright still cannot be enforced unless an application to register it has been filed in the Copyright Office. In addition, if infringement occurs before registration (and more than three months after publication or commercialization), statutory damages and attorney’s fees are no longer available.

Another result of this decision is that designers whose products are routinely “inspired” by the designs of others, should be cautious. The Court has made it clear that some designs applied to clothing may be protectable by copyright.

This case is far from over. The Supreme Court’s decision was based on an appeal of Star Athletica’s Motion for Summary Judgment that the designs were not copyrightable. The District Court granted the motion, and the 6th Circuit reversed. The affirmance by the Supreme Court sends the case back to the District Court for a decision on the merits. At issue, and foreshadowed by the Supreme Court’s footnote 1 on page 11 of the decision, is whether Star Athletica can defeat Varsity’s copyrights on other grounds. Footnote 1 makes it clear that the decision does not “hold that the surface decorations are copyrightable,” only that the surface decorations are eligible for copyright protection based on their “conceptual separability.” The Court, citing Feist, expressed “no opinion on whether these works are sufficiently original to qualify for copyright protection” or “on whether any other prerequisite of a valid copyright has been satisfied.”

Can Star Athletica show that such designs lack originality? Can Star Athletica establish that the designs include colors that are dictated by the schools and shapes that are dictated by the uniform? If so, the designs cannot satisfy the low threshold of originality. Finally, are such designs ubiquitous in the industry and do they predate Varsity, such that they are unprotectable scenes-a-faire?

The fashion industry and legal professionals will continue to monitor this case with great interest.