Edited by: Catherine Holland

In a recent precedential decision, In re University of Miami, Serial No. 86616382 (T.T.A.B. June 6, 2017), the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (the “TTAB”) clarified the scope of the doctrine of trademark mutilation.

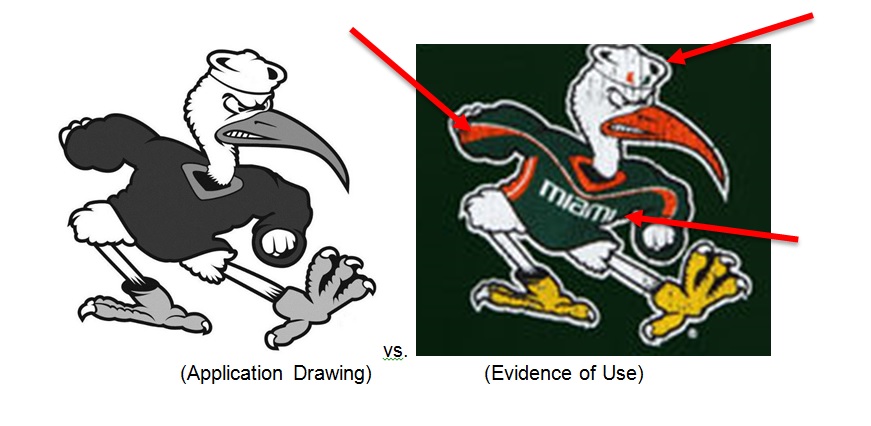

The University of Miami (the “University”) sought to register its logo mark depicting its mascot, Sebastian the Ibis,  , for a variety of clothing products, among other goods and services. To obtain a trademark registration, an applicant must submit a drawing of the mark along with a description of the mark and an appropriate specimen (evidence of use).[1] The University described the mark as an “ibis wearing a hat and a sweater” and submitted the following specimen of use on its sweaters:

, for a variety of clothing products, among other goods and services. To obtain a trademark registration, an applicant must submit a drawing of the mark along with a description of the mark and an appropriate specimen (evidence of use).[1] The University described the mark as an “ibis wearing a hat and a sweater” and submitted the following specimen of use on its sweaters:

The Examining Attorney refused registration of the application as the specimen included additional material such as a “U” as part of the Ibis’s hat, as well as the word “Miami” and striping on the Ibis’s sweatshirt that is not shown in the original application drawing:

Thus, the University had purportedly ‘mutilated’ its mark by “severing part of [the mark] and seeking registration only of that part.” The University appealed to the TTAB, which reversed the Examining Attorney’s decision.

The Board noted that applicants generally have some leeway in selecting a particular mark or logo and can register certain portions of a given mark provided that the portion applied for creates a separate and distinct commercial impression. If the part to be registered does not create a separate and distinct commercial impression, then the application will be refused as an impermissible mutilation of the mark as used in commerce.

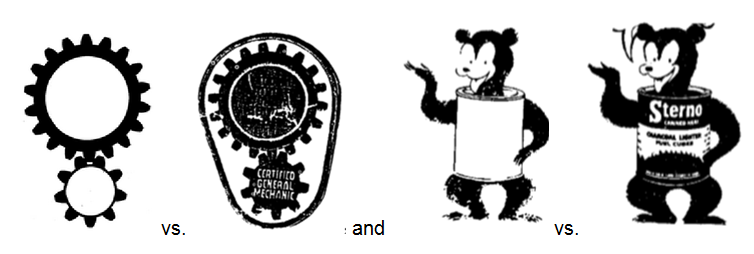

The Board noted that in prior decisions, applicants were permitted to register design marks that did not include accompanying words and were not deemed mutilations, such as the following:

Here, because the mark  creates a separate and distinct commercial impression from the “U” and “Miami” shown in the specimen,

creates a separate and distinct commercial impression from the “U” and “Miami” shown in the specimen,  , this was not a mutilation of the mark as used. In addition, the lack of the stripes that were shown in the specimen but not the drawing were deemed a “minor” alteration.

, this was not a mutilation of the mark as used. In addition, the lack of the stripes that were shown in the specimen but not the drawing were deemed a “minor” alteration.

Accordingly, because the University’s drawing was a “substantially exact representation” of the University’s mark as it is actually used in commerce, this was an acceptable specimen and did not constitute a mutilation of the mark.

Takeaway

This decision shows the importance of periodically reviewing a trademark portfolio, ensuring that key marks are registered, and verifying that the marks used by the company are identical to the marks shown in the registration. Careful attention to these details mitigates the risk that the trademark owner’s applications or specimens of use will be rejected. When attempting to register composite marks or logo marks with literal elements, trademark owners should assess whether to pursue multiple applications that cover different aspects of the mark. If different aspects of the mark can stand alone because they each create a “separate and distinct commercial impression,” then it may be possible to obtain more than one registration for the same mark. This allows the trademark owner more flexibility in using variations of its mark on its goods. If all of the elements of a mark are interwoven and impossible to separate, however, the trademark owner must ensure that the mark it uses in commerce is essentially identical to the mark shown in the registration.

[1] This generally applies to U.S. applications based on Section 1(a) or 1(b) of the Trademark Act and does not apply to foreign applicants that seek registration in the U.S.