Edited by Loni Morrow and Catherine Holland

Airwair, the owner of the Dr. Martens brand, recently launched a series of lawsuits in the Northern District of California to enforce the trade dress of its “iconic boots and shoes.” One lawsuit was filed in October against Wanted Shoes, and one more recently in February against the Steve Madden brand. These recent lawsuits follow the resolution of two AirWair lawsuits filed earlier in the year based on the same marks against Next PLC and Esquire Footwear LLC. The suit against Next resulted in a consent judgment and permanent injunction. In other words, the parties settled and agreed that Next would stop making the infringing boots.

Airwair describes its Dr. Martens boots, shoes, and sandals as featuring a distinctive trade dress including the following features: (1) “yellow stitching in the welt area of the sole,” (2) a two-tone grooved sole edge, (3) the distinctive DMS sole pattern, and (4) a black fabric heel loop. Airwair alleges that the trade dress of its boots and shoes has been used since 1960 and is among “the world’s greatest and most recognizable brands.”

Shown below are exhibits from Airwair’s complaints, comparing Airwair’s Dr. Martens boot to the boots made by Wanted Shoes and Steve Madden. The Next product from the earlier lawsuit that resulted in a consent judgment and permanent injunction is shown as well. The complaints against Steve Madden and Next include claims for violating the trade dress in the Dr. Martens’ sole pattern.

Trade dress is usually defined as the “total image and overall appearance” of a product, or the totality of the elements, and “may include features such as size, shape, color or color combinations, texture, graphics.” Two Pesos, Inc. v. Taco Cabana, Inc., 505 U.S. 763, 764 n.1 (1992). The non-functional features of a product’s shape or packaging (its “trade dress”), may be protectable if they are sufficiently distinctive. The classic example of trade dress is the distinctive Coca-Cola bottle: ![]() .

.

Trade dress is generally divided into two categories: product packaging and product configuration. Product packaging (the box the product comes in) can be inherently distinctive and immediately protectable. On the other hand, product configuration (the shape of a product) is never inherently distinctive, and is only protectable after establishing acquired distinctiveness/secondary meaning.

Design patents are similar to trade dress, as they protect the ornamental appearance of an otherwise functional item. A design patent protects the appearance of an item, and not its structural or utilitarian features. The advantage of a design patent is that there is no need to establish secondary meaning before protection arises. However, unlike trade dress rights that can last as long as the owner continues to use them, design patents are in effect for only15 years. For more information on design patents, see Design Patents – The Often Forgotten, But Useful Protection for Accessories and a Designer’s Timeless and Staple Pieces.

Trade dress is registrable with the USPTO as a trademark or service mark. Federal registration confers significant advantages to the owner in its efforts to stop infringers. Like any trademark, however, an owner can still protect its trade dress without a registration under the common law, provided it can establish the trade dress has acquired distinctiveness.

Product shapes are being protected with ever-increasing frequency. Examples include YOPLAIT® yogurt’s red swirl packaging; DREYER’S® ice cream’s brown and white striped top; the bean shaped window used by Jelly Belly Candy Company; the shape of the VOSS® water bottle and vertical placement of the mark; GOLDFISH® fish-shaped crackers; or MAKER’S MARK® dripping wax seal on bottles. Trade dress has also been used to protect the appearance of a restaurant and the method of displaying wine bottles in a retail wine shop.

In the clothing industry, trade dress may cover the red-sole of a Christian Louboutin shoe, the placement of the red-tab on a pair of Levis jeans, the Burberry check pattern, or the checkered pattern of a Vans shoe.

If the trade dress is non-functional and is either inherently distinctive or has acquired customer recognition from sufficient promotion of the protectable features, it may be registered as a trademark. For example, the shape of a HERSHEY KISS® chocolate, red-sole of a Christian Louboutin shoe; Levi’s red tab; Burberry’s check pattern, and Vans checkerboard pattern have been registered with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. Likewise, Converse has registered the trade dress of its hi-top and regular shoes:

US. Reg. No. 4062112 and US. Reg. No. 4065482

As has ASICS for its shoe trade dress

To help achieve this type of protection, non-functional and distinctive product features or packaging should be selected. These features should then be promoted through “image” advertising or “look for” advertising so that customers recognize the product shape or packaging as a source-identifier and associate it with a single source. Ideally, these elements should also be distinctive and used consistently across product lines.

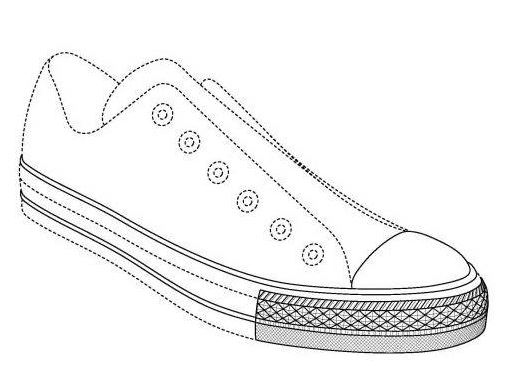

A recent ITC case involving Converse, however, proves that there are limits to trade dress protection. In the Matter of Certain Footwear Products, USITC, 337-TA-936 (2016). In 2014, Converse launched litigation against more than 30 companies over the alleged copying of Converse’s Chuck Taylor shoe. In 2016, the ITC found Converse’s trade dress covered by U.S. Registration No. 4398753 for the midsole design of the Converse shoe “invalid” based on lack of secondary meaning and, therefore, not enforceable in the ITC proceeding. The trade dress covered by U.S. Registration No. 4398753 is shown below and described in the registration as “the design of the two stripes on the midsole of the shoe, the design of the toe cap, the design of the multi-layered toe bumper featuring diamonds and line patterns, and the relative position of these elements to each other.”

The ITC weighed the seven factors relating to secondary meaning, including, (1) the degree and manner of use, (2) the exclusivity of use, (3) the length of use, (4) the degree and manner of sales, advertising, and promotional activities, (5) the effectiveness of the effort to create secondary meaning, (6) deliberate copying, and (7) association of the trade dress with a particular source by actual purchasers. Specifically, the ITC found that the survey evidence relating to the seventh factor, which “provides the ‘strongest and most relevant’ evidence, weighs against a finding of secondary meaning” for that trade dress.

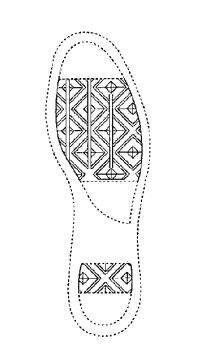

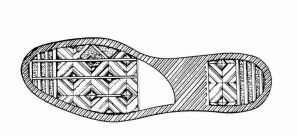

In contrast, two Converse trade dress registrations were held valid in the case: the trade dress covered by U.S. Registration No. 3258103 and the trade dress covered by U.S. Registration No. 1588960 shown below. The trade dress covered by U.S. Registration No. 3258103 “consists of a three dimensional tread design located on the outsole of a shoe” and the trade dress covered by U.S. Registration No. 1588960 “consists of a three dimensional sole of shoe design.” Overall, however, the unenforceability of the midsole trade dress mark can be seen as a blow to Converse’s ability to protect its shoes.

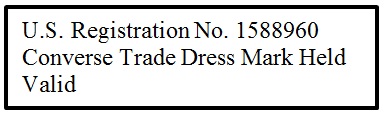

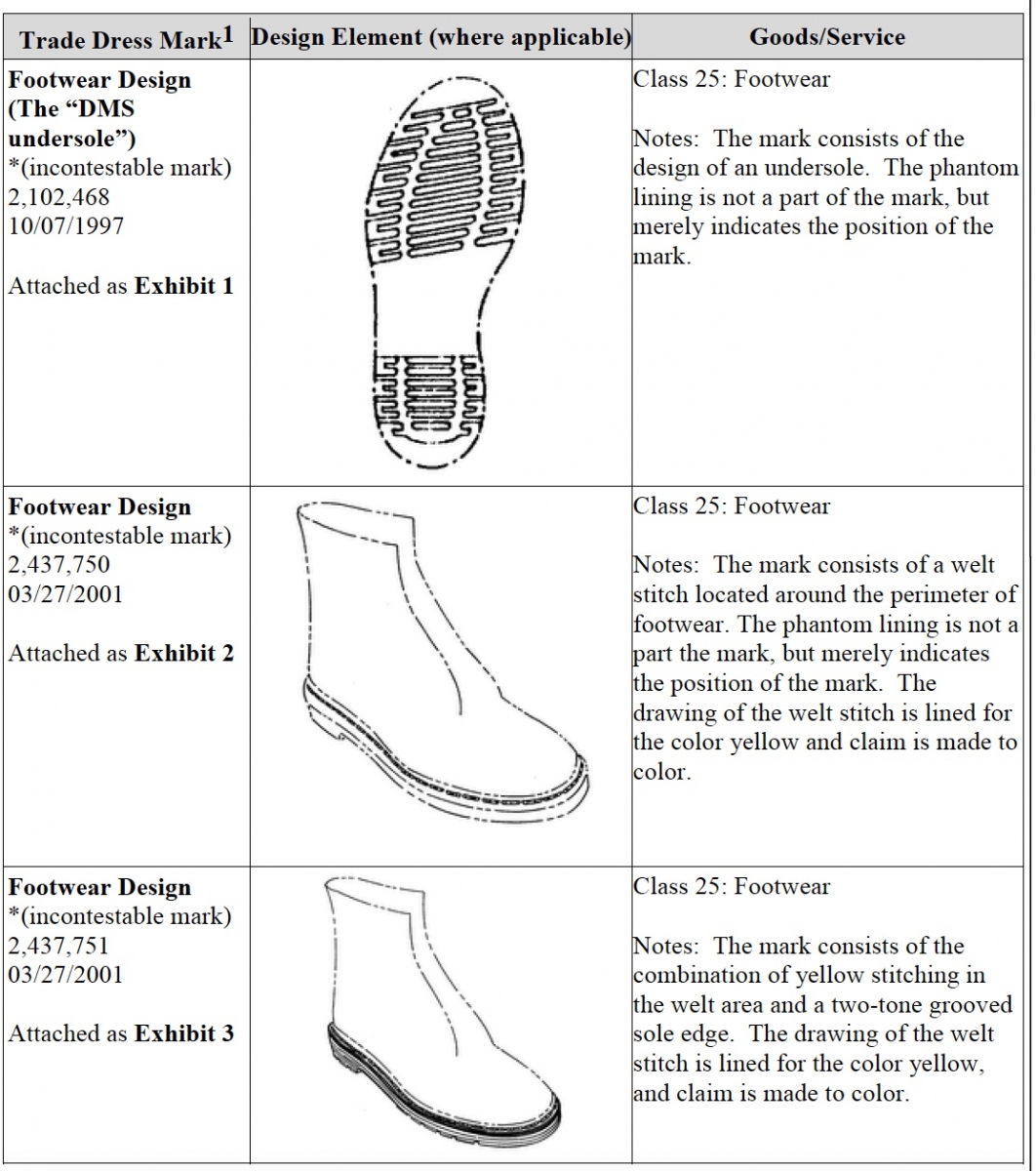

It remains to be seen how AirWair’s Dr. Marten trade dress claim will fare. AirWair’s complaints listed five federal trademark registrations for its trade dress, which are shown below. Many of the trade dress registrations focus on the edge of the shoe’s sole. Multiple registrations cover a “welt stitch” of yellow color, a two-tone grooved sole edge, and longitudinal ribbing on the sole edge with a dark color band over a light color on the outer sole edge.

AirWair alleges that there is significant overlap in the distinctive features that formed the basis for the trade dress infringement claims in the Steve Madden and Wanted Shoes cases. Both cases include claims for unlawful copying of the two-tone grooved sole edge and the heel loop. In the complaint against Wanted Shoes there was an additional claim related to beige stitching in the welt area, and in the Steve Madden case there was an additional claim related to the undersole pattern of the shoe.

In both cases, in addition to its Federal Trademark Infringement claims under Section 32 of the Lanham Act for infringement of a registered mark; AirWair also raised unfair competition and false designation of origin claims under Section 43(a) of the Lanham Act and California state and common law, and a claim for dilution under Section 43(c) of the Lanham Act and California state and common law. For the trademark infringement claims, assuming AirWair’s trademarks are deemed valid and protectable, the cases will turn on whether the allegedly infringing products are likely to cause confusion, or to cause mistake, or to deceive. Likewise, assuming AirWair’s trade dress is distinctive and famous in the United States, the Federal Trademark Dilution claims will turn on whether the allegedly copied products are likely to dilute or blur the distinctiveness of Airwair’s trade dress. Additionally, when a Trademark Dilution claim is made, the court will consider whether the sale of the allegedly diluting products lessens the capacity of AirWair to identify and distinguish its products.

Only time will tell if AirWair’s boots were made for walking, and if those boots are gonna walk all over Wanted Shoes and Steve Madden.