Laboratory-developed tests (“LDTs”) are in vitro diagnostic (“IVDs”) products designed and used within a single clinical laboratory to perform high complexity testing. These tests can identify a wide range of issues from cancer risks to Alzheimer’s diagnoses. Nearly 70% of today’s medical decisions utilize laboratory test results, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The prevalence of LDTs highlights the significant impact they have on the U.S. healthcare system and underscores the need for validity and accuracy.

In-vitro Diagnostics

The FDA, concerned about potential harm to patients, sought increased oversight of these products by classifying them as medical devices. This change was prudent, the FDA argued, due to the growing number of tests offered and the lack of assurance that they are effective. This situation raises the potential for harm from unnecessary, delayed, or forgone treatment based on inaccurate test results.

In response to this situation, the FDA proposed a new rule on October 3, 2023, which explicitly listed IVDs as devices under the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. This new classification would end the prior enforcement discretion for these tests and instead include them within the medical device regulatory regime. This regime requires registration, listing the device, potential premarket notification or approval, clinical studies, quality systems regulation, labeling requirements, and finally, reporting on deaths or serious injuries caused by the device or that the device contributed to.

This rule change met resistance from industry players who argued the move was overly burdensome and would result in limited access to testing and stifled innovation. ARUP Laboratories, an opponent of the rule, cited research conducted by itself and the Spencer Fox Eccles School of Medicine at the University of Utah, claiming 93.9% of all tests ordered in 2021 were approved and authorized by the FDA.

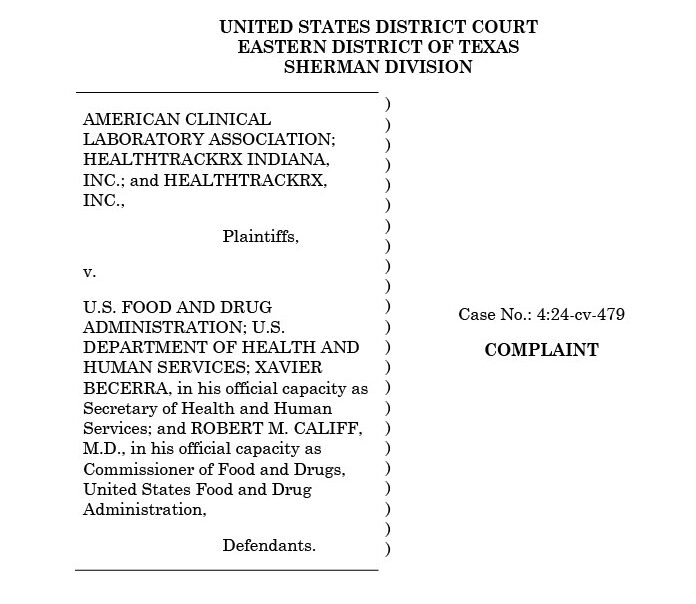

Despite industry pushback, the FDA issued the final rule on May 6, 2024, following extensive negotiations. This version of the regulation included a phase-out policy, which afforded companies time to adjust to the new scheme. After issuance, the American Clinical Laboratory Association (“ACLA”), HealthTrackRx, and the Association for Molecular Pathology (“AMP”) filed suit. They asserted that the FDA exceeded its statutory authority by regulating professional testing services and that the rule was arbitrary and capricious.

In March of this year, Judge Sean Jordan of the Eastern District of Texas ruled against the FDA, vacating and setting aside the final rule in its entirety and remanding it back to the Secretary of Health and Human Services for further consideration. Judge Jordan stated that the FDA does not have authority to regulate LDTs. Instead, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (“CMS”) holds that authority, as codified by the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (“CLIA”). The Judge also found the existing framework through the CLIA to be sufficient for regulating LDTs.

On remand, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the Secretary of Health and Human Services, officially reverted the rule to its prior text in a Federal Register entry dated September 19, 2025, ministerially ending this regulatory scheme in its current form.