Edited by Loni Morrow and Catherine Holland

In the fashion and beauty world, the copying of higher-priced brands is widespread. While in fashion, the term for copies of designer products is “knockoffs,” in beauty, the term is “dupes.” Whether it is a colloquial use of the word “dupe” or an abbreviation of “duplicate,” to beauty brand consumers the word dupe has come to mean a cheaper alternative to higher-end products. Beauty dupes allow bargain shoppers to experience department store makeup at drug store prices. Countless blog posts, Pinterest pins and YouTube videos compare products from brands like MAC, Nars and Yves Saint Laurent to products from more budget-friendly brands such as Revlon, Maybelline and E.L.F. Dupes have even inspired Instagram accounts like @dupethat, which provides over one million followers with dupes of makeup, haircare, skincare and other beauty-related products, as well as hashtags like #makeupdupes, which includes more than 20,000 posts on Instagram. Beauty gurus and social media influencers claim that the dupes offer the same look, and sometimes even the same quality, as the higher-end products. While consumers take such claims with a grain of salt, they actively seek out and purchase the affordable $7 lipstick with the same color and texture as the $37 designer lipstick.

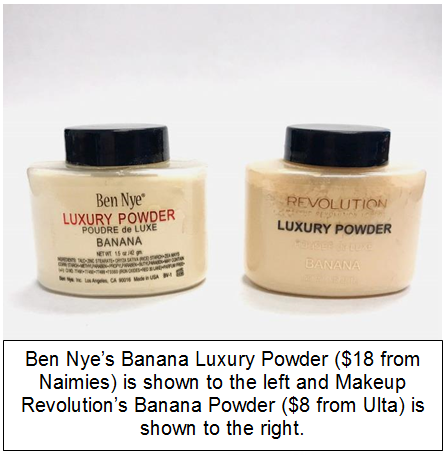

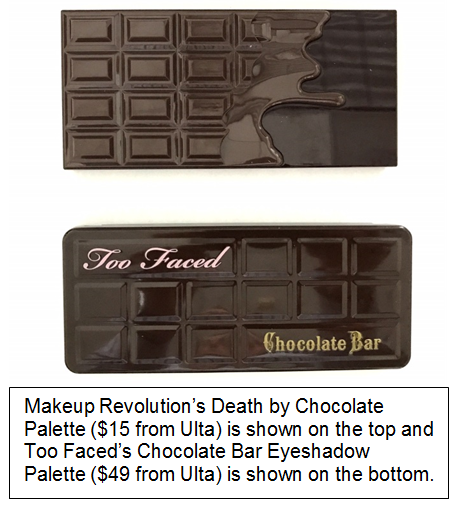

The concept of the dupe has become a mainstay of the $56.2 billion beauty industry in the United States. Lower-end beauty brands, capitalizing on the enthusiasm for dupes, are offering products that have characteristics or qualities identical, or at least very similar, to the popular products of their higher-end counterparts. While most brands copy only characteristics of the beauty product itself, some brands take “duping” one step further by also copying the product packaging. Popular drug store beauty brand, Makeup Revolution, has caught the attention of consumers and designer makeup brands with its duping of both makeup products and packaging. As shown to the right, Makeup Revolution offers alternatives to higher-priced products, such as face powders, eyeshadow palettes, and other beauty products, that are very similar in appearance while sometimes being half the price.

Makeup Revolution and other similar brands have been publicly criticized for this type of imitation. Katherine von Drachenberg, the creator of Kat Von D Beauty, pointed out on her Instagram (@thekatvond) that Makeup Revolution’s dupe of her eye-shadow palette copied not only the shades but also the specific placement of those shades and the name of the palette. While the Kat Von D palette is named “Shade + Light Eye Contour,” the Makeup Revolution palette is named “Ultra Eye Contour – Light and Shade.” Von Drachenberg took to YouTube to express her problems with dupe-culture. She made a distinction between dupes and “rip-offs.” While she agreed that affordable alternatives to beauty products can be a positive, she characterized the copying of color selection, layout, and naming as “straight up plagiarism.”

It is unsurprising that, after spending large amounts of time and resources on product research, development and marketing, brands dislike it when others copy their beauty products. Consumers, on the other hand, likely appreciate the diversity and accessibility of products that are similar to higher priced products. However, consumers may also have concerns regarding dupes. When dupes imitate the distinctive qualities of a good, including the look and feel of the product and its packaging, consumers may be confused as to the source and make false assumptions as to quality and performance of a product. The concerns of brands and consumers, combined with the ethical issues of copying, call into question the legality of beauty product duping. Are beauty dupes infringing on the trademark rights of the copied brands?

Trademark law protects those aspects of a product that identify its source. In other words, what is it about the product that makes consumers think it comes from one particular manufacturer? Trademark law recognizes that consumers often rely upon product design and/or product packaging as an identifier of the source of the product. For this reason, product design and product packaging can be protected by trademark law as trade dress.

To be protectable as trade dress, the product packaging must be both non-functional and distinctive. If the product packaging is sufficiently unique, it may be deemed to be inherently distinctive, and registrable without additional evidence showing that consumers perceive the packaging to be proprietary to one company.

To obtain protection for the appearance of the product itself, however, evidence will be required that the product design has acquired distinctiveness in the mind of the consumer. Such evidence can include a declaration attesting to the substantially exclusive and continuous use of the product in commerce for five years, and evidence of significant sales and advertising of the product. When it is difficult to determine whether it is the product packaging or the product design for which protection is being sought, such “ambiguous” trade dress will be treated as product design, and the evidence of acquired distinctiveness will be required.

In many cases, the product design or the product packaging may lack distinctiveness or secondary meaning. This means that consumers would not perceive it as an indication of the source of the goods. Consumers may recognize the iconic J’Adore fragrance bottle and the green and pink Great Lash mascara tube, and associate them with their brands, Dior and Maybelline, respectively. However, if the design or packaging is not highly unique or unusual, or has not gained recognition over time or through “look for” marketing, it may be difficult to show source-indicating function as required for trade dress protection. As such, beauty brands may have difficulty establishing trade dress rights, whether in court or when seeking to register the product design or packaging design with the U.S. Trademark Office.

Even if the product design or the packaging design is sufficiently distinctive to be registered, some packaging designs and even more product designs are functional and, therefore, not registrable. Where the packaging design or the design of a product is functional, it is ineligible for trademark protection. For example, a lipstick tube that indicates the color of the lipstick inside could be considered functional.

Due to the hurdles in establishing and enforcing trade dress rights, beauty brands may be reluctant to take action against other companies that copy not only their product, but also the look and feel of their products. The uncertainty as to whether beauty products will be protected through trade dress may compel brands to rely on the strength of their brand names and the quality of their products. These beauty brands hope that consumers will purchase their original goods rather than the more affordable imitations.

Dupes and knockoffs have become a significant part of the fashion and beauty industries. When developing new products, the higher-end brands should consider adopting intellectual property strategies that will improve their ability to establish exclusive rights, which will allow them to enforce their rights against the imitators. Such strategies can include look-for advertising or other techniques that will strengthen the association of the look and feel of the product or the product’s packaging with the source of the product. Solidifying this association, and consistently enforcing the resulting trademark rights, can improve the odds for the originator and innovator. Finally, while not discussed in this article, design patents also may be available to protect innovative packaging appearances that are new and not obvious. A well-rounded intellectual property strategy can be used to provide some distance between the competition and the originator’s product and product packaging, thereby allowing the originator to recoup some of their investment in their product and product packaging research and development.