Unitary patents in Europe

The European unitary patent and Unitary Patent Court (UPC) are slated to go into effect in early 2017. These monumental changes will have a significant impact on the ways patent rights are obtained and enforced in Europe. Traditional European patents themselves are not enforceable, but can allow a patentee to validate, maintain, and enforce a patent in nearly any combination of over 40 different countries, for which costs, formalities, and patent enforcement venues and laws differ by individual country. On the other hand, the unitary patent itself will be enforceable in each of 26 member states), will be subject to a consolidated set of fee and formality requirements, and will fall under the jurisdiction of a single unitary patent court (UPC). Several cost and strategic considerations for the unitary patent are of particular interest to biotechnology applicants.

To obtain a unitary patent, an applicant in the European Patent Office can file an explicit request for a unitary patent within one month of grant. Alternatively, for the time being, an applicant can proceed with a traditional European patent instead. Non-European applicants that wish to obtain a unitary patent will retain the options of entering Europe via either a direct filing to the European Patent Office, or the European Regional phase of a Patent Cooperation Treaty application. As an alternative to the unitary patent, applicants will continue to have the option of filing national patent applications in individual European countries. For biotechnology applicants filing in Europe, certain features of European patents, such as the unavailability of “method of treatment claims,” and stringent requirements for literal basis are expected to generally apply to the unitary patent.

Countries that are covered by the unitary patent

The countries for the unitary patent are limited to (but do not automatically include) member states of the European Union, and differ from the current member states of the European Patent Convention. Notably, Albania, Croatia, Iceland, Lichtenstein, Monaco, Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, San Marino, Serbia, Spain, Switzerland, and Turkey will not participate in the unitary patent, but these countries remain members of the European Patent Convention. As such, traditional European patents and national patents will still be available in these countries, but enforcement will be through national courts.

The United Kingdom’s ongoing “Brexit” from the European Union will also have an impact on the unitary patent. Assuming the United Kingdom completes its exit from the European Union, the United Kingdom may still remain a member of the European Patent Convention, which is separate from the European Union. Consequently, traditional European Patents will continue to be available, as will national patents; however, the unitary patent (and enforcement via the UPC) will not be available in the United Kingdom.

Potential cost savings via unitary patents

At the grant and maintenance phases, the unitary patent will affect costs, and can potentially offer cost savings for lengthy biotechnology patent applications, as well as, large portfolios that would typically be validated in a large number of countries.

For traditional European patents, 17 member states require translations into their local language. Under the unitary patent, translations of English-language applications will not be required in Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Greece, Italy, Poland, Romania, or Slovakia. It is noted for a “transitional period” of up to 12 years, at the grant phase of a unitary patent, English-language applicants must file a single translation into any official language of the European Union. Minimizing translation costs, which are often on a per-page basis, can provide a substantial cost savings for lengthy biotechnology patent applications. Since Spain, San Marino, and Serbia do not participate in the unitary patent, coverage in these countries can be obtained with a national filing and/or traditional European patent, and will require a translation.

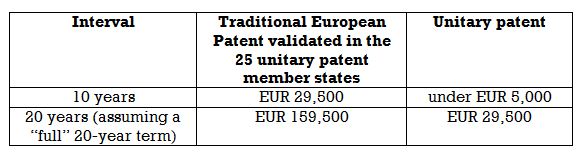

Moreover, under the traditional European patent grant system, progressively more expensive maintenance fees must be paid in each of the individual validation states. On the other hand, maintenance fees under the unitary patent will be the sum total of the maintenance fees for the four countries most frequently validated (Germany, France, United Kingdom, and the Netherlands). As illustrated below, the accumulated cost of renewing a unitary patent will be substantially less than the corresponding maintenance fees for a traditional European patent in all 25 unitary member states:

Estimated accumulated maintenance costs (per the EPO)

Enforcement of unitary patents

Thus, for applicants that would typically validate a European patent in at least Germany, France, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands (and patents for pharmaceuticals are frequently validated in many more countries), the current unitary patent fee structure offers longer-term cost savings on maintenance fees, in addition to the more immediate savings on translations. Moreover, for therapeutic products with long development and regulatory cycles, patentees often must decide early whether to validate and maintain foundational patents in a large number of countries. The prospect of lower maintenance fees can make it more cost-effective to secure patent rights in many European countries, pending the outcome of a regulatory review. On the other hand, the “all-or-nothing” approach of the unitary patent prevents patentees from cutting back on renewals later in the patent term.

Both unitary patents and traditional European patents will be enforceable in the UPC. The jurisdiction of the UPC will automatically apply to existing European patents and grants of currently-pending European applications unless an applicant files an explicit request to opt out. Applicants and patentees for current European patents will have the option to opt out of the UPC for a “sunrise” period of at least 7 years, which could begin as early as late 2016 (which would allow for an opt-out period extending at least until late 2023). However, for a unitary patent itself, there is no option to opt out of the UPC. Additionally, even after the opt-out period ends, applicants wishing to avoid the unitary patent and/or the UPC can still file individual national patent applications in European countries of interest.

For therapeutic products that may ultimately be marketed in many countries, consolidating enforcement proceedings into a single court has the potential to streamline the proceedings and reduce costs. Litigating under a single system of harmonized laws in the UPC may also make it easier for global patentees to clarify that they are taking consistent positions in the United States and Europe. Small to mid-size companies may benefit from the consolidating of litigation into the UPC compared to the prospect of enforcing or defending in multiple jurisdictions against a larger competitor with extensive resources. On the other hand, as the UPC is a new and untried system, litigation outcomes in the UPC may be less predictable than in more established national venues.

Patent term considerations for biotechnology companies

An important consideration for biotechnology companies in Europe is the availability of Supplementary Protection Certificates (SPCs), which can provide extension of patent term to compensate for delays during regulatory review periods, analogous to patent term extension in the United States. In particular, SPCs can offer up to five years of protection for pharmaceutical products subject to regulatory review (plus an additional 6 months for certain pediatric products). However, the current UPC regime currently does not contain a provision for enforcement or invalidation of SPCs. The European Commission has encouraged the incorporation of SPCs into the unitary patent framework. However, for the time being, current applicants and patentees for pharmaceutical products in Europe have an interest in continuing to monitor the availability of SPCs under the UPC, so that they may elect to optout prior to the end of the seven-year “sunrise” period, if SPCs appear to be unavailable.

Summary

The complex set of advantages and considerations for a unitary patent will depend, in part, on an applicant’s particular technology, business model, product development cycle, competitive landscape, and options for enforcement. For the time being, selecting a strategy for protection in Europe will require a tailored analysis of a particular applicant’s technology, the applicable legal standard, and short-term and long-term goals. In summary:

- The following 26 European states will participate in the unitary patent: Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Germany, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, United Kingdom, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Latvia, Malta, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia, Slovakia, Sweden;

- The following European Patent Convention states (for which a traditional European Patent is available) will not participate in the unitary patent: Albania, Croatia, Iceland, Lichtenstein, Monaco, Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, San Marino, Serbia, Spain, Switzerland, and Turkey;

- English-language applications will no longer need to be translated for Unitary Patents in Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Estonia, Greece, Poland, Romania, and Slovakia;

- Maintenance fees for a unitary patent may be substantially lower for applicants that would otherwise validate a traditional European patent in at least four jurisdictions.

- The Unitary Patent Court will have jurisdiction over traditional European Patents, as well as, Unitary Patents; and

- Existing European Patents and applications will automatically fall under the jurisdiction of the UPC unless applicants explicitly opt out. The opt-out period is expected to run until at least late 2023.

- Supplementary Protection Certificates (term extension for pharmaceutical regulatory review) are not currently available for unitary patents.