Introduction

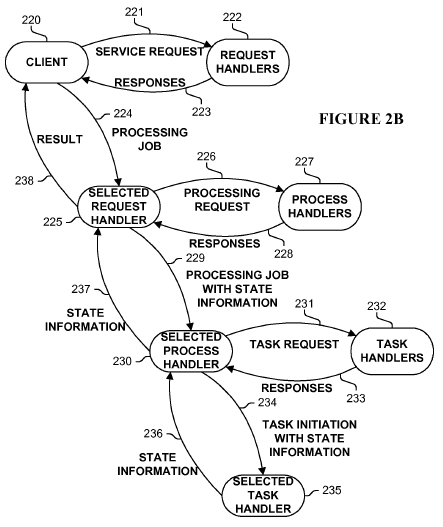

On July 19, 2016, the District Court for the Western District of Washington (“Court”) dismissed a patent suit because the asserted patents (U.S. Patent Nos. 8,682,959 and 9,049,267) cover ineligible subject matter. See Appistry, Inc., v. Amazon.com, Inc., et al., Case No. C15-1416RAJ (W.D. Wash. July 19, 2016) (“Order”). The patents in suit relate to using “[a] hive of computing engines . . . to process information.” See ‘959 Patent at 8:32-33. To do so, the claimed inventions use “a plurality of networked computers” to “process[] a plurality of processing jobs in a distributed manner.” See ‘959 Patent at 31:30-31; ‘267 Patent at 28:8-9. The claimed processing is accomplished using “a request handler, a plurality of process handlers, and a plurality of task handlers.” See ‘959 Patent at 31:32-34; ‘267 Patent at 28:10-12; id. at Fig. 2B.

On July 19, 2016, the District Court for the Western District of Washington (“Court”) dismissed a patent suit because the asserted patents (U.S. Patent Nos. 8,682,959 and 9,049,267) cover ineligible subject matter. See Appistry, Inc., v. Amazon.com, Inc., et al., Case No. C15-1416RAJ (W.D. Wash. July 19, 2016) (“Order”). The patents in suit relate to using “[a] hive of computing engines . . . to process information.” See ‘959 Patent at 8:32-33. To do so, the claimed inventions use “a plurality of networked computers” to “process[] a plurality of processing jobs in a distributed manner.” See ‘959 Patent at 31:30-31; ‘267 Patent at 28:8-9. The claimed processing is accomplished using “a request handler, a plurality of process handlers, and a plurality of task handlers.” See ‘959 Patent at 31:32-34; ‘267 Patent at 28:10-12; id. at Fig. 2B.

Patent Eligibility Inquiry

In 2014, the Supreme Court reiterated that laws of nature, natural phenomena, and abstract ideas are not patentable, because they are the basic tools of scientific and technological work. See Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank Int’l, 134 S. Ct. 2347, 2354 (2014). According to Alice, to determine patent eligibility, courts must (i) first determine whether the claim is directed to one of these patent-ineligible concepts (“step one”), and if so, (ii) then determine whether the claim includes any additional elements that transform the nature of the claim into a patent-eligible application (“step two”). See Alice at 2355. If a claim is determined to be directed to a patent-ineligible concept in step one and determined to lack any additional elements that transform the nature of the claim into a patent-eligible application in step two, the claim is ineligible for patent protection.

Step One: Directed to an Abstract Idea

In step one, the Court found that the claims in the ‘959 and ‘267 patents are directed to the abstract idea of “distributed processing akin to the military’s command and control system.” Order at 4-5. Appistry argued that the claims are not directed to abstract ideas because they do not claim mathematical equations or business problems. The Court rejected this argument, noting that the operative question is whether the patent claims are directed toward an abstract idea, not whether the invention could be classified into one of Appistry’s categories. Appistry also argued that the claims cannot be performed by humans. The Court rejected this argument as well. “[T]he fact that inventions here are implemented on computers or only exist in the computing realm does not save them” from patent ineligibility. See Order at 7.

Step Two: No Inventive Concept

In step two, the Court found that the claims do little more than task generic computers with generic functions, noting there is nothing inventive about “completing a task or process by distributing it downward via a hierarchical series of ‘handlers’ located on generic computers spread throughout a generic network.” Order at 8-9. Although Appistry argued that the claimed invention provides improved speed, efficiency, and reliability, the Court rejected this argument. The Court stated that the actual systems and methods through which such advantages are achieved are well understood, routine, and purely conventional and do not supply an inventive concept separate from the underlying abstract idea. Order at 9. For these reasons, the Court found that the two patents cover ineligible subject matter.

This case illustrates that software-implemented inventions can fail to satisfy 101 even if those inventions improve the functioning of a computer such as by increasing speed, efficiency, and reliability, if those improvements are achieved through conventional, known computer techniques.